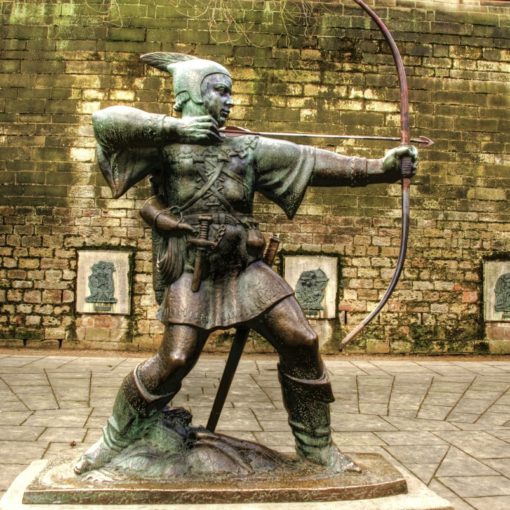

The bow is one of man’s oldest inventions. Today there cannot be many inventions dating back at least to the last ice age, which are still used in an almost unchanged form. Yet that is true of the bow – more specifically the English, or European longbow. Our modern age has brought technical innovations and there are mass-produced bows and arrows today incorporating synthetic materials and designs resulting from the application of modern science and engineering. These are to many archers’ tastes, but there are many who do not care for them. Modern archery has been valuable in introducing people to archery in an affordable way at least. However as we enter the 3rd millennium AD, there probably has never been a time when more archers through choice have eschewed modern technology and returned to the archetypal ancient weapon – a simple stave of wood bent into an arc, eternally functional and beautiful in its simplicity.

Many nations have distinguished themselves in the use of the bow. We are fortunate in Britain that we have a rich tradition of our own. However, in nations as diverse as Hungary, Korea, Mongolia, the Native American nations and many others, the same renaissance of their archery traditions is gathering pace. There is also a mutual interest in each others’ ancient archery cultures and it is indeed something to rejoice that the bow now can bring peoples together in a shared passion. It has been said that the bow now is ‘the weapon of peace’. It is something to be deeply proud of that the weapon which has written many bloody chapters in the past now brings enthusiasts together in a way which bridges nation and culture.

We are also at a very exciting time as understanding of the truly ancient archery is growing and being recreated practically. Instead of a dusty, academic, book-based movement, this instead is a practical one where the past is being relearned by recreation in reality by dedicated researchers and participants. In Britain, the turning point of our understanding of our longbow tradition was undoubtedly the discovery of the wreck of the Mary Rose warship dating from the Tudor era, which was in fact the twighlight of the longbow as a military weapon. Almost as soon as the amazingly well preserved bows – and not so well preserved arrows were brought to the surface, many of our common preconceptions about English archery were shaken. Yet as we learn more, we realise there is so much more we do not know and which is yet to be discovered.

Myths and legends about the English longbow have abounded for centuries. Yet it is still something very poorly understood by the common person in this country. Many still labour under misconceptions – most of which originated more in Victorian romanticism than in historical fact. Bar-room bores still trot out old clichés and insist they are incontrovertible fact. Some people even seem to have an emotional investment in their beliefs and cling to them, refusing to accept new findings even if they are backed up by high-quality empirical evidence. There are exciting developments all the time now in the field of the English longbow as we understand it today in its ancient form, and how it is being revived today as a vibrant and exciting ‘new’ style of archery.